Published: 1 September 2022

Publications

Prostaglandin-associated periorbitopathy

Prescriber Update 43(3): 35–36

September 2022

The Medicines Adverse Reactions Committee (MARC) reviewed the risk of

prostaglandin-associated periorbitopathy (PAP) at the 190th

meeting in June 2022.

The MARC considered that the evidence showed the risk of PAP was a class effect. Medsafe has asked the sponsors to update their data sheets with information on this adverse reaction.

Ocular prostaglandin analogues

Ocular prostaglandin analogues are a class of medicines commonly used to treat glaucoma.1 They bind to prostaglandin F (FP) receptors in the eye, leading to increased aqueous outflow through the uveoscleral pathway.2 The increased outflow reduces the elevated intraocular pressure associated with glaucoma.2,3

Bimatoprost, travoprost and latanoprost are the ocular prostaglandin analogues currently available in New Zealand.

Prostaglandin-associated periorbitopathy (PAP)

The term ‘prostaglandin-associated periorbitopathy’ describes clinical and cosmetic changes in the eye associated with prostaglandin analogues.4 Patients may experience one or more of the following:4

- deepening of the upper eyelid sulcus

- flattening of the lower eyelid bags

- upper eyelid ptosis (drooping eyelid5)

- orbital fat atrophy

- mild enophthalmos (posterior displacement of the eye6)

- inferior scleral show (sclera visible between the cornea and lower eyelid margin7)

- tight orbit

- ciliary hypertrichosis

- hyperpigmentation of the periorbital skin

- dermatochalasis (redundant eyelid skin5).

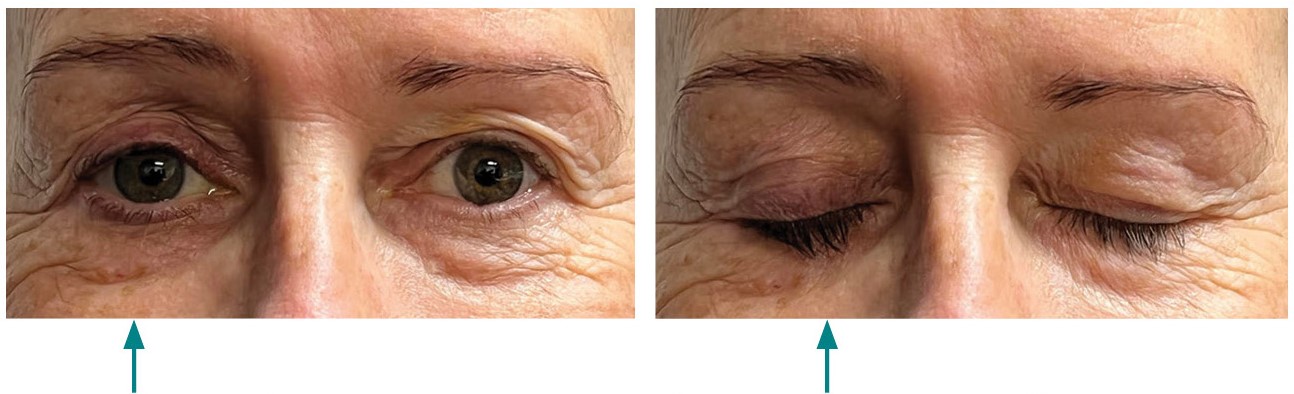

Figure 1 shows a patient with PAP in one eye.

The risk of PAP is likely to be the highest for bimatoprost and the lowest for latanoprost.8 It has been reported in more than 10 percent of patients treated with bimatoprost.1 Clinical and cosmetic changes can occur as early as one month after starting treatment.1 The changes may be partially or fully reversible upon discontinuation or switching to alternative treatments.1

The mechanism of prostaglandin-associated periorbitopathy is not fully understood. Stimulation of the FP receptors by prostaglandin analogues may inhibit adipogenesis, leading to orbital fat atrophy.8

Figure 1: Patient with prostaglandin-associated periorbitopathy in one eye

Following unilateral treatment with a prostaglandin analogue, the patient developed PAP in the treated eye (arrow).

The images are used with the kind permission of the patient.

Advice for healthcare professionals1

Before starting treatment, inform patients of the possibility of changes to the eye during treatment. These changes are typically mild, can occur as early as one month after initiation of treatment and may cause impaired field of vision. Patients should also be aware that unilateral treatment may lead to differences in appearance between the eyes (as seen in Figure 1).

More information

References

- Multichem NZ Limited. 2019. Bimatoprost Multichem New Zealand Data Sheet 7 June 2022. URL: medsafe.govt.nz/profs/Datasheet/b/BimatoprostMultichemeyedrops.pdf (accessed 28 July 2022).

- Ghate D, Camras CB. The Pharmacology of Prostaglandin Analogues. URL: entokey.com/the-pharmacology-of-prostaglandin-analogues/ (accessed 4 July 2022).

- Labib BA. 2018. The purpose of prostaglandins. Review of Optometry. URL: www.reviewofoptometry.com/article/the-purpose-of-prostaglandins (accessed 4 July 2022).

- Sakata R, Chang P-Y, Sung KR, et al. 2021. Prostaglandin-associated periorbitopathy syndrome (PAPS): addressing an unmet clinical need. Seminars in Ophthalmology 37(4): 447–54. DOI: 10.1080/08820538.2021.2003824 (accessed 27 June 2022).

- Lee MS. 2021. Overview of ptosis. In: UpToDate 17 March 2021. URL: uptodate.com/contents/overview-of-ptosis (accessed 27 June 2022).

- Soparkar CN. 2018. Enophthlamos. In: Medscape: Drugs & Diseases, Ophthalmology 20 September 2018. URL: emedicine.medscape.com/article/1218656-overview (accessed 27 June 2022).

- Loeb R. 1988. Scleral show. Aesthetic Plastic Surgery 12(3): 165–70. URL: pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/3189035/ (accessed 27 June 2022).

- Patradul C, Tantisevi V and Manassakorn A. 2017. Factors related to prostaglandin-associated periorbitopathy in glaucoma patients. Asia Pacific Journal of Ophthalmology (Philadelphia, PA) 6(3): 238–42. DOI: 10.22608/APO.2016108 (accessed 5 April 2022).