Published: 6 March 2014

Publications

Medicine Induced Anaphylaxis - Reporting is Vital!

Prescriber Update 35(1): 2–3

March 2014

Anaphylaxis is a life-threatening, systemic hypersensitivity reaction that

can occur with a wide range of medicines. Healthcare professionals are advised

to report all cases of suspected or confirmed medicine induced anaphylaxis

to the Centre for Adverse Reactions Monitoring (CARM) even if the reaction

is well known.

Reporting will enable a 'Danger' to be entered against the patient's NHI on the Medical Warning System to alert other healthcare professionals to the patient's allergy1.

Medical Warning System

The Medical Warning System is a national alert service that is linked to National Health Index (NHI) numbers1. CARM enters information on serious and/or life threatening adverse reactions into this system as either a 'Warning' or a 'Danger'. Anaphylaxis is always entered as a 'Danger'.

Whenever the patient's NHI is accessed, the 'Danger' is automatically highlighted to ensure that healthcare professionals are aware of the patient's allergy. Unfortunately, although the system is visible to DHB's, the Medical Warning System is not currently accessible to the majority of GPs.

Reports to CARM

From 1 January 2000 until 31 December 2013, CARM received a total of 1433 reports of anaphylactic or anaphylactoid reactions. The majority of patients were women (63%) and most patients had made a full recovery (>90%) by the time of reporting to CARM.

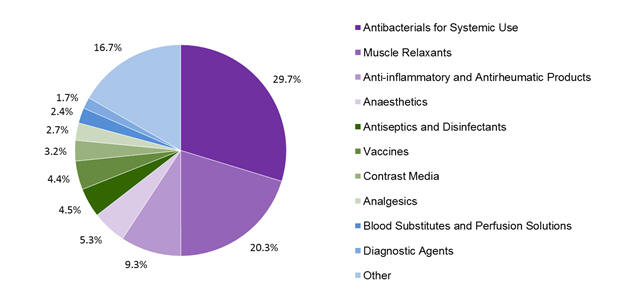

In New Zealand, anaphylaxis is most commonly reported following the administration of antibiotics, neuromuscular blocking agents (muscle relaxants), NSAIDs and anaesthetics (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Top 10 classes of medicines associated with anaphylaxis in the CARM database

While the pattern of reporting in New Zealand is consistent with that in the published literature, the proportion of reports in each of these classes is lower than in many studies. The lower rate may indicate that New Zealand healthcare professionals are less likely to report cases associated with medicines that are well known to cause anaphylaxis.

The most commonly implicated individual medicines were rocuronium (10%), amoxicillin/clavulanic acid (7%), suxamethonium (7%), diclofenac (5%) and cefazolin (5%).

Of note, 4.5% of the reports were for anaphylaxis to antiseptics such as chlorhexidine which may not be well recognised as a cause of anaphylaxis2.

Anaphylaxis Terminology

The term anaphylaxis has traditionally been used to describe IgE mediated allergic reactions and the term anaphylactoid reaction has been used to describe non-IgE mediated reactions. However, as the two types of reactions are not clinically distinguishable and are treated in the same way, anaphylaxis is now used to describe both categories of reactions.

In 2010, the World Allergy Organization divided anaphylaxis into three categories3.

- Immunologic anaphylaxis (IgE mediated or non-IgE mediated).

- Non-immunologic anaphylaxis.

- Idiopathic anaphylaxis.

Medicines can cause both immunologic and non-immunologic anaphylaxis.

Diagnosis

The diagnosis of anaphylaxis can be difficult. However, anaphylaxis is likely if the following features are present4,5.

- Acute onset and/or rapid progression of symptoms.

- Life-threatening airway compromise (swelling, hoarseness, stridor) and/or breathing difficulties (rapid breathing, wheeze, fatigue, cyanosis) and/or circulatory compromise (pale, clammy, faintness, hypotension).Skin reactions (eg, rash, urticaria, angioedema).

Treatment

Intramuscular adrenaline is the core treatment for anaphylaxis. It should be given immediately to all patients with life-threatening clinical features. Anaphylaxis treatment algorithms should be followed4-6.

Long term management should include patient education, referral for allergy testing and consideration of a Medic Alert bracelet.

For further advice on the diagnosis and management of anaphylaxis please refer to the guidelines produced by the Best Practice Advocacy Centre (BPAC), NZ Resuscitation Council and Starship Children's Hospital4-6.

References

- Ministry of Health. 2012. Medical Warning System. 28 March 2012. URL: www.health.govt.nz/nz-health-statistics/national-collections-and-surveys/collections/medical-warning-system (accessed 5 February 2014).

- Medsafe. 2013. Chlorhexidine — risk of anaphylaxis. Prescriber Update 34(2): 22. URL: www.medsafe.govt.nz/profs/PUArticles/June2013Chlorhexidine.htm (accessed 5 February 2014).

- Lieberman PL. 2014. Recognition and First-Line Treatment of Anaphylaxis. The American Journal of Medicine 127: S6-S11.

- Best Practice Advocacy Centre. 2008. The management of anaphylaxis in primary care. Best Practice Journal 18: 10-19. URL: www.bpac.org.nz/BPJ/2008/December/anaphylaxis.aspx#5 (accessed 5 February 2014).

- New Zealand Resuscitation Council Inc. 2011. Adult Anaphylaxis August 2011. URL: www.nzrc.org.nz/assets/Uploads/Newsletters/Adult-Anaphylaxis-Algorithm.pdf (accessed 5 February 2014).

- Sinclair J. 2010. Starship Children's Health Clinical Guideline: Anaphylaxis. March 2010. URL: www.adhb.govt.nz/starshipclinicalguidelines/_Documents/Anaphylaxis.pdf (accessed 5 February 2014).